One of the topics I’ve been getting really passionate about lately is algorithmic music: also called live coding, algomusic, or algorave depending on emphasis.

No matter what, though, algomusic is essentially this: writing code that generates patterns which generate music.

In algomusic, performances involving writing code in real-time to generate the music, changing the code over the course of the performance—sometimes entirely improvisationally & sometimes from pre-written pieces and snippets—in order to create a progression to the music.

It’s actually an incredibly interesting world and one that’s far easier to break into than you might think!

I want to start by talking about two different algorithmic music systems that I think represent very different ways of treating algomusic. The first is Sonic Pi

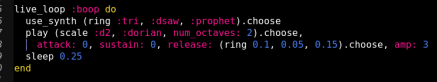

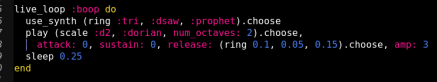

In Sonic Pi, the fundamental model is that you create imperative loops that all run concurrently. They have explicit timings through both the use of a sleep function as well as synchronization primitives between the various threads. Sonic Pi is really simple to install, get started with, and teach to people who have zero programming background.

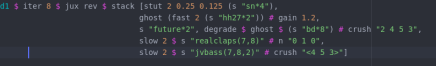

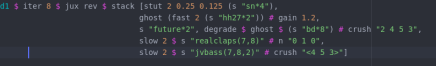

The other end of the spectrum, and probably my favorite live coding system, is TidalCycles which has a very distinctly functional programming feel. Not just because it was written in Haskell, either, but because its built around the composition of functions to output a pattern, which is itself essentially a function from time to sound events. Rather than being set around explicit time TidalCycles is organized around “cycles”. You write patterns that each fit into a cycle, which ends up being a very natural way to think about the flow of time. TidalCycles isn’t necessarily difficult to set up, but it does require more work than Sonic Pi. On the other hand, its pattern language is absolutely brilliant: you can create so many complex melodies and rhythms in a single line of code.

What I want to talk about the rest of this post is why I think algomusic is so interesting.

First, one thing I find fascinating as an ex-PL researcher is that the programming involved in algomusic isn’t even very complex!

Mind you, the actual libraries themselves are big impressive pieces of software, but the actual user experience involves very simple code: Sonic Pi could be boiled down to a small imperative fragment of Ruby and Tidal could be recast as a lambda-calc + Pattern monad & primitives.

That’s really neat! It says that there’s a very sonicly expressive core to algomusic, at least as it currently exists.

This also means that algomusic is fairly accessible. It’s easy to get started with experimentation even without being an experienced programmer. And, experimentation is a really key point to how algomusic works in practice. It’s a fundamentally different way of programming than most typical coding.

After all, for a lot of computation we have a clear picture of the intended object of what the program should do when it’s done. There may be surprises along the way, you may change your mind, you may come up with a novel way to solve a problem, but you’re not going to be experimenting with code to see what happens in the same way.

What’s interesting about algomusic is that, much like art, it frequently doesn’t have something concrete as its intended object. There is experimentation, improvisation, a feedback process that involves the senses and the body, and the possibility of surprise. It’s not just that you’re writing code to make art but you’re writing code like you’re making art.

Now, there is one area of Serious Computer Science that has a very similar feel to live coding, at least to me: working with a theorem prover! Yes, you may have a theorem in mind that you hope to prove but frequently working with a theorem prover is far more experimental and improvisational.

You try definitions, see what can be proved, imagine properties and see if they hold, look at what goes wrongs and gain intuition to help you bridge the gap between definitions and properties.

Is it surprising that using a theorem prover might feel similar to coding art? I don’t think so. Plenty of people before me have argued that creativity in mathematics is like the creativity in the arts.

I want to be clear, though, I’m not talking about a binary of experience but of a spectrum. I just think that live coding is rather interestingly on one far end of the spectrum.

So, I’ve been talking about from a languages and a philosophic perspective what I find interesting about algomusic but what about from the perspective of, well, music?

Part of it is that code has potentially far more expressiveness than a traditional symbolic notation for music. Not only can you give note and percussion orderings but you can very concisely describe ways to create complex structures from the basic patterns.

In TidalCycles, you can take a pattern like s "bd*2 hh27", which is two bass drums samples followed by a hi-hat, and then apply the following change sometimesBy 0.25 (off 0.125 (# speed 0.5)) $ s "bd*2 hh27" which now says that 25% of the time we follow the beat by a pitched down echo of itself at a delay of an eighth note.

That’s not easy to describe in traditional notation!

At the same time, code in algomusic is less like a score than a single note of a rather strange instrument, because the code creates the music all at once in one action on the performer’s part. This sounds weird with respect to a classical instrument but has some precedent in synthesizers with arpeggiation modes, where a single key held down plays through a pattern of notes. An algomusic score, strangely, would then have to look more like a sequence of diffs of the code over time like a version control system might keep.

I’m not aware of any such system that currently exists but it opens up a lot of novel possibilities for how algorithmic music can be recorded, performed, and played back apart from the moment of performance.

Even more, algomusic allows us to ask interesting questions about time in relation to our experience of music. For example, Alex McLean—creator of Tidal—had a blog post recently asking questions about what it would look like for a system like Tidal to have something like record scratching where you can non-linearly shift back and forth in time. I think not only is that just a cool idea it’s also fascinating since music in a way is felt time. Playing around with the way we feel time is fundamentally a way of getting at the essence of what music even is!

Now, to wrap up these various threads I think that algorithmic music is exciting because it involves a novel twist on every subject it touches on. It’s different as music, different as coding, different as performance. It’s exciting to be a part of something that is so young that there aren’t even rules yet & so open we can’t even guess what the limits could be.